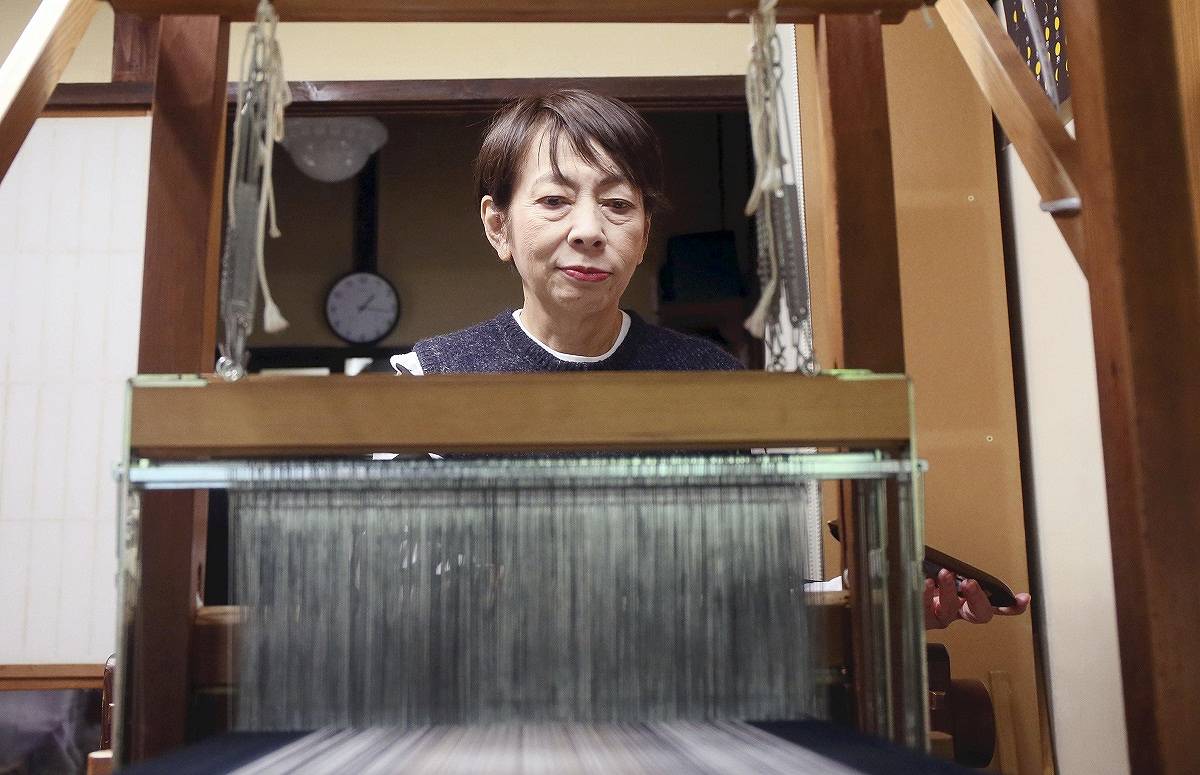

In November, Noriko Tsuiki talks about the attractiveness of Kokura-ori textiles in her studio in Kitakyushu.

15:00 JST, March 10, 2024

FUKUOKA — Kokura-ori is a cotton fabric that was once used to make samurai hakama pants and other products, but fell out of fashion in the early Showa era (1926-1989). Kitakyushu-based textile dye artist Noriko Tsuiki, 71, revived the textile 40 years ago and pursues the beauty of the vertically striped patterns, created using many different colored threads. Her designs are well suited to a wide range of products beyond textiles, allowing Kokura-ori to evolve into a material culture that represents Kitakyushu.

In a studio in a mountainous part of the Yahata-Higashi district, Kitakyushu looms in time with classical music.

Kokura-ori textiles are produced by repeatedly weaving warps through wefts. To weave one traditional obi wing, the act of inserting wefts into a weaving machine must be repeated more than 30,000 times. “Since Kokura-ori uses high-density warp, inserting the wefts requires some force,” Tsuiki said. The level of concentration required to effectively weave evenly can last for up to an hour. To facilitate timing, the studio has more than 100 CDs, including operas and folk music. When a CD ends, she takes a short break to make mental and physical preparations and then continues weaving.

Tsuiki weaves Kokura-ori in her studio in Kitakyushu in November.

The production of Kokura-ori textiles began in the Buzen Kokura domain in the Edo period (1603-1867). The textile was so strong that it would be impenetrable to spears. Kokura-ori fabric was widely available and used for samurai hakama pants and obi sashes. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Edo shogunate, is said to have worn a Kokura-ori haori coat when he practiced falconry. In the Meiji era (1868-1912), the textile was used to make school uniforms. However, counterfeit or low-quality products were produced in many parts of the country, and Japan was hit by a wave of mechanization. Under these conditions, Kokura-ori production ceased in the early Showa era.

Tsuiki came into contact with the long-gone and largely forgotten textiles at the age of 30, when she pursued a career in dyeing and weaving. She found a four-inch strip of fabric in an antique shop she frequented in Kitakyushu. The fabric shone, like tanned leather, and had a smooth texture. When she picked up the old rug with the stylish vertical striped patterns, she was moved and thought: ‘This is what I was looking for.’

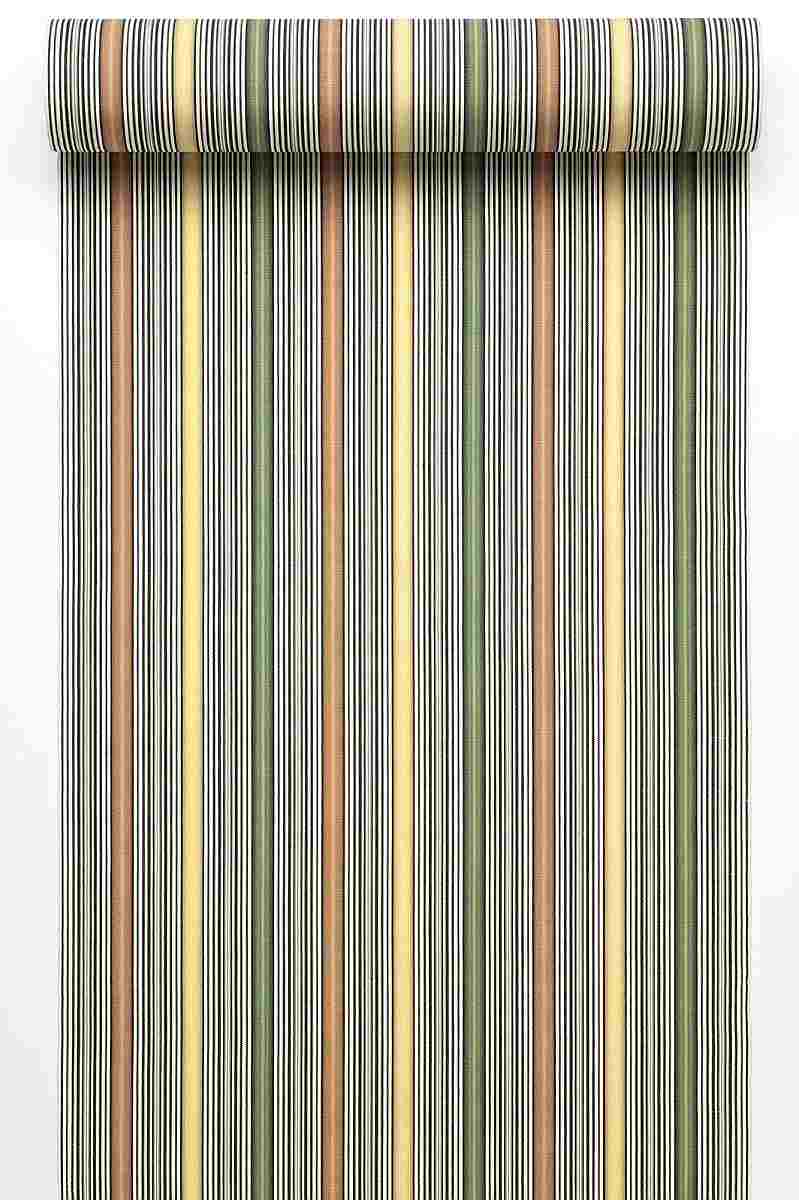

The unique patterns are created by using more warp threads than weft threads. She read the few documents on textiles she could find in libraries and museums. She also analyzed, in collaboration with a research institute, how it was woven and the thickness of the threads. However, she failed to recreate the correct texture even though she wove the same way. After nearly two years of trial and error, in 1984 she finally recreated the Kokura-ori textile by spreading 2,160 warp threads, almost three times the number of weft threads, over a width of about 35 centimeters, and developed a technique for weaving with a density where the loom barely moves.

Tsuiki’s Kokura-ori fabric

Tsuiki was born in 1952 in the town of Yahata, today’s Yahata-Higashi district, Kitakyushu. She learned, among other things, dyeing and weaving techniques on the island of Kume in Okinawa Prefecture. She oversees the design process of “Kokura Shima Shima”, a shop that produces machine-woven products. In 2008, she received the Commissioner’s Award from the Cultural Affairs Agency at the Exhibition on Traditional Handicrafts, Dyeing and Weaving in Japan.

“I want many people to use it as a general purpose product,” she said. With that goal in mind, she has made efforts to develop machine-woven fabrics. She has sought to introduce Kokura-ori fabrics into clothing, fashion accessories and home decor, while also producing works of art. “I want to create vertical striped patterns that no one has ever seen before,” she said. She has continued her dogged pursuit even after turning 70.