Craftsmen reproduce a scene in which glue and dye left on fabric are washed away in a practice called mizumoto by a river.

15:30 JST, November 19, 2023

Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, famous for its towering skyscrapers and neon lights adorning the Kabukicho district, is also home to a traditional kimono dyeing industry.

The area is known for the production of kimono fabric that is dyed using traditional methods such as Edo-komon and Edo-yuzen. A look into the area’s history reveals why the Edo period (1603-1867) tradition originated in Shinjuku.

At an apartment complex in Kamiochiai’s western Shinjuku district, an old-fashioned machine spewed white steam as it smoothed out wrinkles on dyed fabric with a roller. The process is called “yunoshi”.

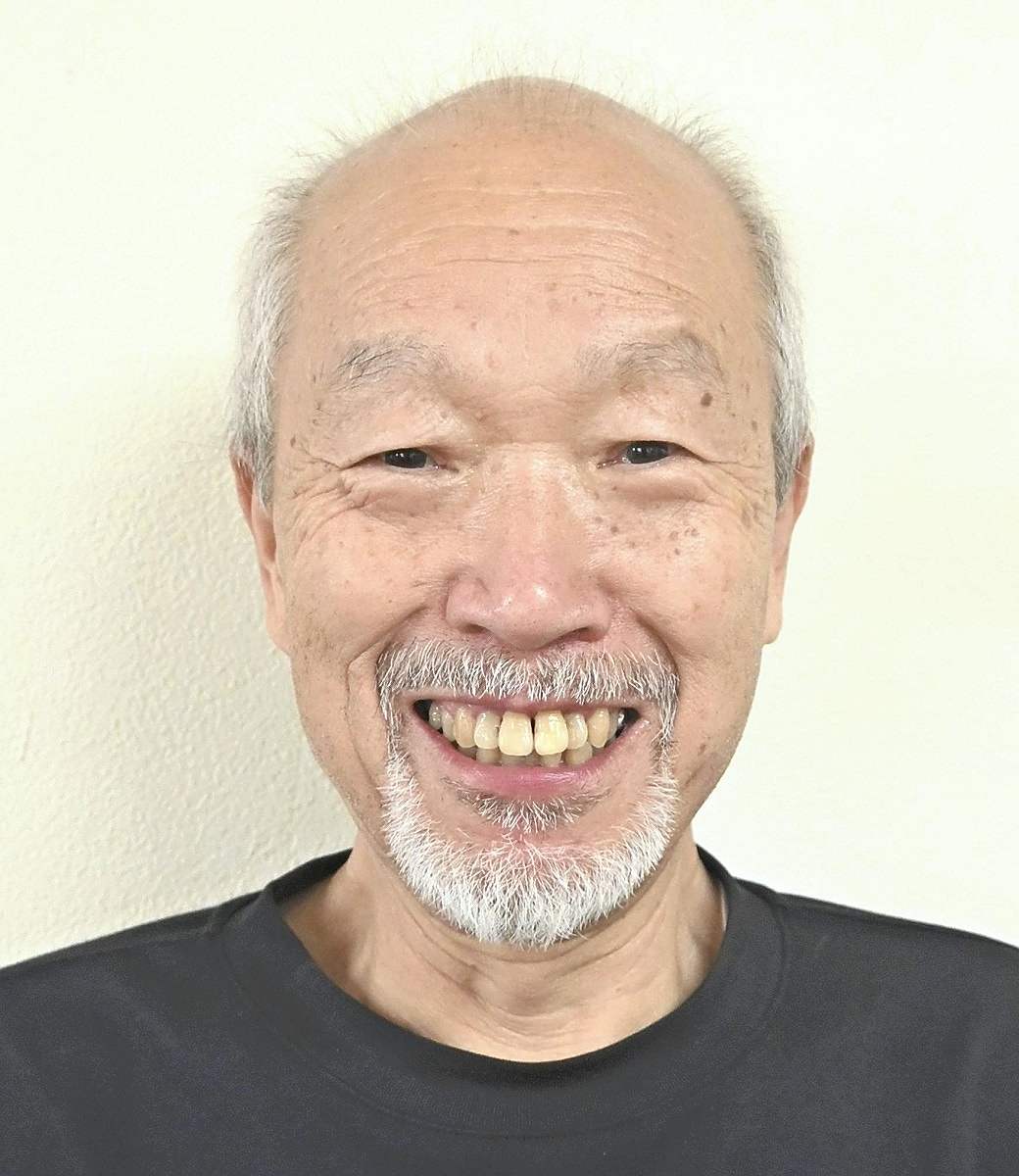

Satoshi Yoshizawa

“The connection between Shinjuku and dyeing is hidden in the name Ochiai,” said Satoshi Yoshizawa, 59, a third-generation yunoshi craftsman and chairman of the Shinjuku City Dyeing Council.

According to Yoshizawa, the district was named Ochiai because the Myoshoji and Kanda rivers that flow through the district “converge” there (ochiau in Japanese). The dyeing process requires a large amount of water to rinse off the dye and glue. Therefore, paint companies set up their branches along the rivers to gain access to a good water supply.

During the Edo period, the area stretching between the Kanda and Sumida rivers, which flow through the Kanda and Asakusa districts, was the center of the dye industry. The current town name Kandakonya in Chiyoda district suggests that the area around Kanda was home to many konya, or paint shops, during the Edo period.

The most advanced fashion district during the Edo period was today’s Nihonbashi area in Tokyo, where kimono shops such as Echigoya ran their stores. It is said that kimono shops ordered fabrics with trendy patterns from Konya in Kanda and Asakusa.

As time passed from the Meiji era (1868-1912) to the Taisho era (1912-1926), the dye industry in the Kanda area began to decline. As Kanda and Asakusa became busy districts, the water quality of the Kanda River deteriorated. It also became difficult for workshops to secure sufficient land. Dyers looking for clean water and large tracts of land ended up in Shinjuku, located upriver.

Shinjuku’s paint industry flourished from the post-war period until the early 1960s. Modern and stylish Edo-yuzen kimonos were more popular than those made using Kyoto’s Kyo-yuzen dyeing techniques and Ishikawa Prefecture’s Kaga-yuzen dyeing techniques. It is said that there were about 200 dyeing studios along the Kanda River.

At that time, craftsmen would rinse away the glue and dye left on kimono fabric in a river. This practice, called ‘mizumoto’, caused colorful fabrics to bob in the water.

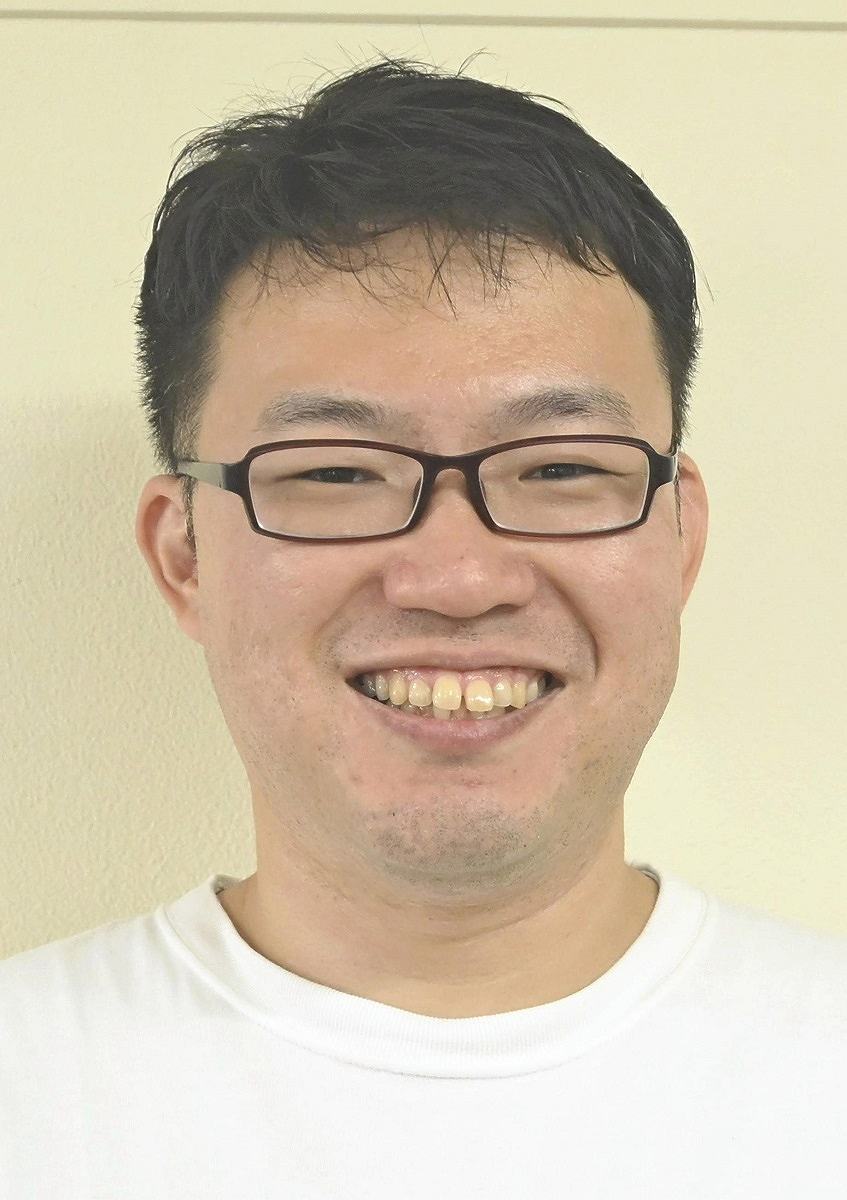

Hideji Nebashi

“Stretches of beautiful kimono fabric were stretched and washed in the water, covering the surface of the river from bank to bank, creating colorful landscapes. It was beautiful when the fabrics waved on the poles,” said Hideji Nebashi, 73, who runs the Chiwata Senko dyeing studio, located in Tokyo’s Takadanobaba district. As the fifth generation of a family producing Edo-komon fabrics, he has observed the transition of the dyeing industry.

Since the mid-1960s, urbanization resulted in a rapid decline of the Kanda River due to water pollution. The mizumoto process was criticized after the dyes used in the process were deemed contaminants, and in 1971 laws were introduced to ban the process. The beautiful scenes eventually disappeared.

The Westernization of lifestyle has also accelerated change. Western clothing styles began to take off in the 1970s, causing the demand for kimono to decline dramatically, resulting in a large number of stores going out of business. Membership of the Shinjuku City Dyeing Council, an organization of dyeing company operators, fell to fifty, less than half of what it had been at its peak.

Yet the tradition has not disappeared from the neighborhood. Many workshops have been converted into apartments, but the traditional techniques have been passed down from generation to generation.

Nebashi runs his workshop on the first and fifth floors of an apartment building. Now he washes dyed fabrics in a water tank, resulting in the occasional phone call from his water supplier asking about leaks due to the amount of water used.

Ryōichi Nebashi

The next generation of dyers is also nourished. Nebashi’s eldest son Ryoichi, 34, is the sixth generation of the family in the business. He learned how to paint from his father six years ago. Ryoichi’s works, which combine traditional techniques with modern designs, have been highly praised. An obi he submitted for a national exhibition of traditional crafts open to public submissions in 2022 won the top-tier Prime Minister’s Prize.

Ryoichi said he initially had no intention of taking over the family business, but instead worked at a medical equipment manufacturer, designing operating rooms and other facilities. He discovered his interest in making things while working with artisans, and now he uses social media to spread the appeal of kimono and dyed fabrics.

“I hope more young people will become interested in kimono through the craftsmen’s skills and their stories,” Ryoichi said.

A craftsman stretches fabric by applying steam in his workshop in Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo, on September 12.